Seeing Nature: Sarah Ormonde & John Wolseley

In Events/Exhibitions May 10, 2017

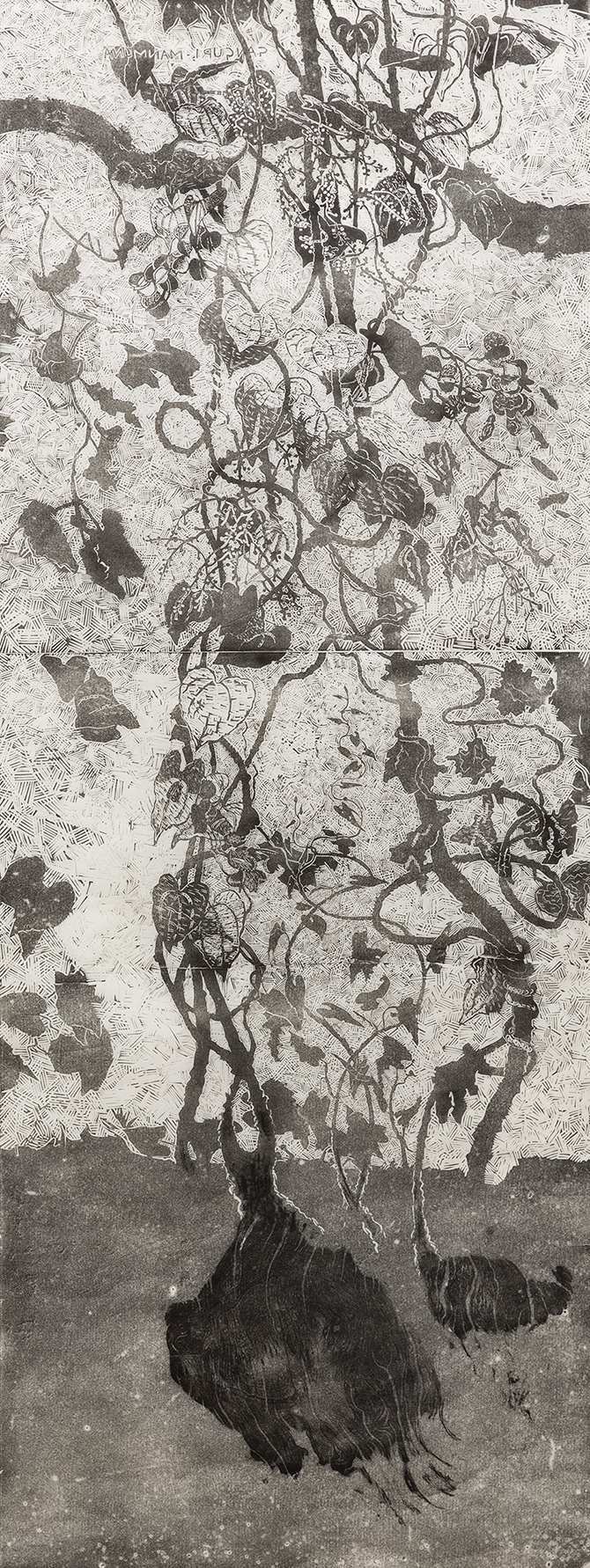

The fulsome statements the artists make about the experiences and observations that underlie their work speak of an intimate identification with the minutae of the natural world. The artists note that just as they make use of mud, sand and wood to make things (art and studio buildings) so too are termites, beetles and birds busily making their own structures (burrows, mounds) from these same materials. To most graphically make this point, fragments of termite mounds have been fired in the kiln and exhibited in ceramic form, while sections of tree trunks with termite burrowing are exhibited alongside the frottage derived prints. The “collaboration” that the artists talk about is inclusive of these creations of the insect world.

In this we can see an idea of Gaia, that is, that nature is a unified and self-governing organism operating in kind of mystical realm beyond conventional science. “I feel my work is about trying to reconnect with those big, frightening but creative forces that are the dynamic of the world we live in”, 1 Wolseley has said. The artist believes we are of the earth: an idea made manifest by the materiality, organic form, earth colours and patterns of Ormonde’s ceramics. But a problem in identifying so intimately with nature as the artists do, is that nature, as represented in the world of termites and other micro life forms, can appear as if on a distancing pedestal.

Perhaps a more inclusive way of regarding nature is to view it as one with reality. In this view, comprehensively set out in the writings of American environmental aesthetics philosopher Arnold Berleant, ourselves, the forests and creatures within them, the cars in our streets, supermarkets and everything else in the world, make up the one interconnected reality. This view argues that everything impacts on everything else: the human is necessarily featured (just as we impact on climate, climate impacts on us – hence climate change).

So far as making art is concerned, this way of thinking about our place in nature is well expressed in plein air painting. The artist places him or herself within the landscape and the ensuing painting represents a bonding of the observed (the subject) and the observer (the artist). The painting documents the interconnectedness between the two; a sense of belonging, of “being there”, is conveyed, and the presence of the observer is acknowledged. An artist who asserts this idea, in ambitiously scaled paintings up to 5 metres wide, is Mary Tonkin. Her immersive paintings are made in the forest of the Dandenong Ranges, where she lives and has her studio.

Nature does not necessarily inspire sensual delight or a sense of belonging in contemporary art. A contradictory set of responses may be invoked, or a Gothic-like strangeness or sense of disturbance may permeate the work. The artist may convey an idea of nature and culture (ourselves) as separate and binary opposites. To represent our relationship with nature from this perspective is to acknowledge a gap, perhaps an existential gap, that expresses uncertainty about how much we can know or possess of the world.

A sense of nature’s separateness may take the form of an otherness loaded with spiritual associations and yearnings. Hence the ubiquity of the void in landscape painting, both in the nineteenth century (for example the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich) and today (particularly where the painting is sourced from photography and other media).

It is not uncommon to find contemporary artists representing our place in nature with an ambiguous mix of the existential, the void, beauty, yearning, and an edgy disconnect all in the same work. These are qualities which feature in the work of Rick Amor: an artist who has deeply immersed himself in the visual world, and who continues to this day to regularly paint plein air, while also representing a personal vision that draws inspiration from cinema and crime novels.

Back to Sarah Ormonde and John Wolseley: the artists’ celebration of nature – grounded in a contemporary discourse of the ecological – also echoes pre-modern responses, when eighteenth and nineteenth century European explorations of nature and New World landscapes aroused intense curiosity. The botanical recordings of Joseph Banks, who accompanied Captain Cook on the Endeavour, and the geological drawings of John Ruskin, the art critic who championed J.M.W. Turner, come to mind when looking at Wolseley’s signature highly detailed drawings (however, these are not on display in this exhibition).

The exhibition also invites associations with a pre-modern conception of beauty, where beauty is held to be a quality or element intrinsic to nature (which can be discerned by us to the extent our awareness allows). This concept of beauty seems to be at odds with the modern idea – associated with the ground-breaking philosophical writings of the late eighteenth century German philosopher Immanuel Kant – that beauty is not a discoverable ingredient in things, but is in the eye of the beholder. Beauty, said Kant, was a quality of perception – it was experienced subjectively – and could not be objectively ascertained.

Asserting that termite burrows are beautiful is a necessarily subjective view; for the termite mounds in the exhibition are no longer termite mounds, but ceramic objects in a gallery context, and anything in a gallery context is no longer what it was outside that context. The claim that these objects represent a collaboration with nature strikes me as fanciful. However, Ormonde’s and Wolseley’s work is an interesting collaboration between these two artists, and the exhibition can awaken our aesthetic curiosity to the microstructures of nature, so that we experience them in a different and more thoughtful way.

Dry Sand, Wet Mud, Moving Earth, Falkner Gallery, 35 Templeton Street Castlemaine (VIC) until 21 May 2017 – falknergallery.com.au

References: 1. John Wolseley, quoted in Artist Profile, Summer 2007, p. 31