Image: Two old artists looking for shellfish – John Wolseley and Mulkun Wirrpanda, opening, Australian Galleries. All photos courtesy of Sasha Grishin

Landscape art as a contemporary art form

By Professor Sasha Grishin AM

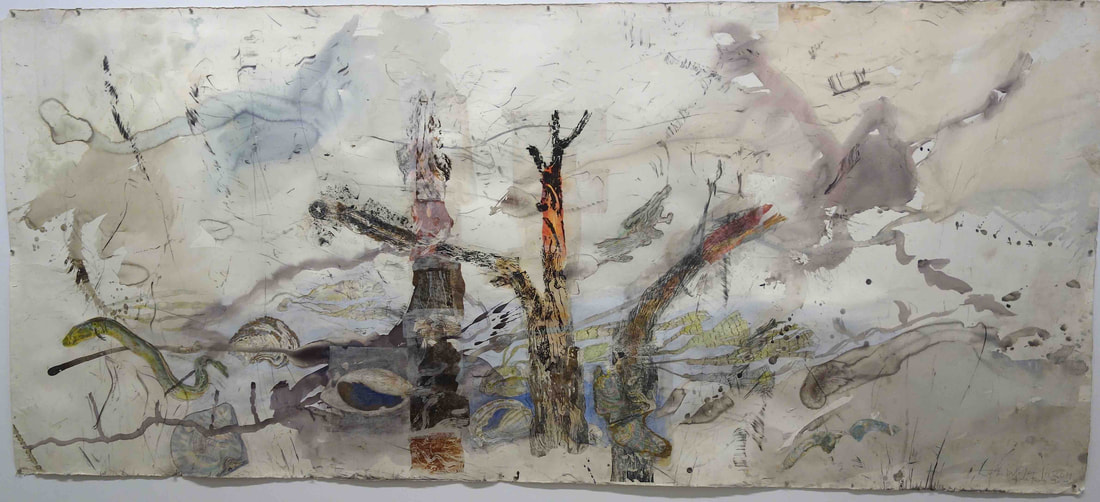

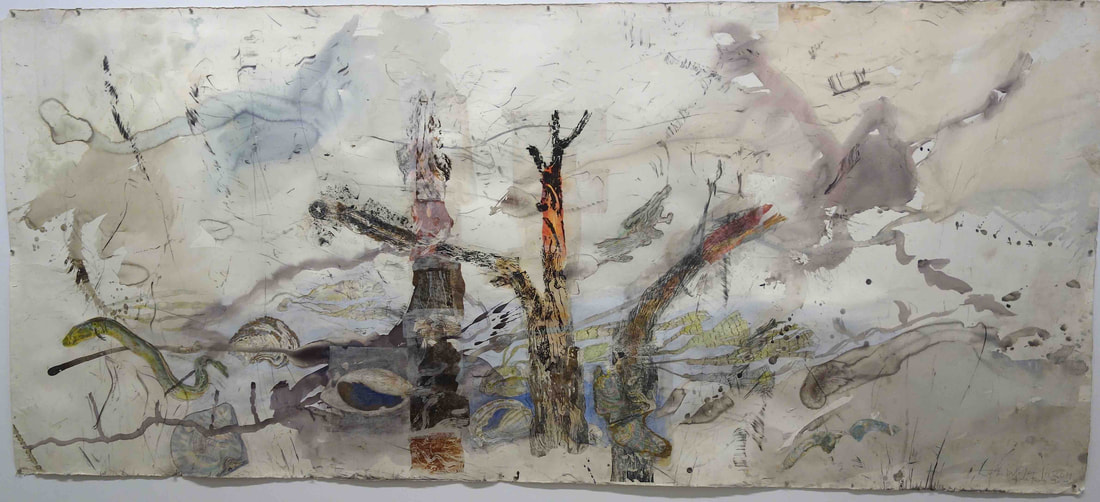

John Wolseley, Umwelt – The life world of the Mangrove oyster, the Teredo worm and the Giant Marbled eel, 2019, watercolour, carbonized wood, graphite, relief prints and chine-collé on paper, 153cm x 346cm

John Wolseley, Umwelt – The life world of the Mangrove oyster, the Teredo worm and the Giant Marbled eel, 2019, watercolour, carbonized wood, graphite, relief prints and chine-collé on paper, 153cm x 346cm

In the 21st century, landscape art in Australia, and elsewhere in the western world, seemed increasingly on the nose in serious art circles. There was a general rejection of landscapes of ownership and possession that stemmed out of the colonial tradition; also the Hans Heysen gum tree looked tired through decades of repetition by technically untrained enthusiasts, while Fred Williams’ modernist landscapes were brilliant in the hands of the master, but became somewhat lame and repetitive through the efforts of his many admirers. Arthur Boyd, Sidney Nolan, John Olsen and Rosalie Gascoigne were some of the lone mavericks that stamped their vision on the Australian landscape in the 20th century. Indigenous art did primarily deal with the landscape, but it introduced an almost entirely new rulebook to depicting country that had little relevance to the previous traditions of Australian and European landscape art. Australian 21st century landscape artists who have made us stop in our tracks and take note have been few in number – the theistic universal visions of William Robinson provide one such example. A few days ago, I came across an impressive and unusual exhibition that brought together three artists – John Wolseley, Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda and Mary Tonkin – all involved with the landscape.

John Wolseley has for several decades been Australia’s preeminent landscape and environmental artist – a lyrical poet and a prophet who challenges some of the assumptions that we make about our future and our coexistence with our environment.The basic distinction between a landscape artist, in the old-fashioned understanding, and an environmental artist, is that a landscape artist stands in front of something to capture, convey or depict it, while an environmental artist is part of the landscape or environment and seeks to convey it, its rhythms and patterns, from the inside.

John Wolseley, Umwelt – The life world of the Mangrove oyster, the Teredo worm and the Giant Marbled eel, 2019, detail

John Wolseley, Umwelt – The life world of the Mangrove oyster, the Teredo worm and the Giant Marbled eel, 2019, detail

Wolseley since the 1970s has sought various strategies through which he could explore the oneness with the environment – a collaboration with nature. He has allowed animals to waddle over his drawings, burnt branches to leave their secret marks over sheets of paper that he has danced through bushfire-ravished environments, he has frottaged the traces that glaciers have left on rock faces and has allowed the patterns caused by burrowing worms in tree trunks to be transferred as prints onto his papers.In recent years, Wolseley has been fascinated by the theories of Jakob von Uexküll, and the concept of umwelt and how creatures perceive their own environments. He speaks of ‘inscapes’, in preference to landscapes, with the idea of seeing things from the inside out, rather than from the outside in.

John Wolseley, Mangrove branch with Teredo worm mollusc tunnels, 2019, unique relief print with worm engraved log on stand, 57cm x 104.5cm

John Wolseley, Mangrove branch with Teredo worm mollusc tunnels, 2019, unique relief print with worm engraved log on stand, 57cm x 104.5cm

In 2009, Wolseley was adopted by Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda – the daughter of the great Yolgnu leader Dhakiyarr Wirrpanda, and an elder and an artist – as a ‘brother’, a member of the Dhuḏi-Djapu clan of the Dhuwa moiety where she anointed him with the name Laŋgurrk. This is a larval grub that lives in mud and yams near freshwater billabongs. Since then, the two artists have collaborated on four exhibitions, including the huge touring

Miḏawarr | Harvest: The Art of Mulkun Wirrpanda and John Wolseley show developed by the National Museum of Australia. The present exhibition at the Australian Galleries in Melbourne marks their most recent collaborative venture, this time devoted to shellfish (Maypal) of East Arnhem Land. Mulkuṉ paints the species as she knows them, in a secular way, combining their naturalistic form with their rhythm, personality and taste, and finding expression in beautifully painted barks and larrakitj poles surrounded by the teeming life of the Arafura Sea.

Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda, Gathul (Mangroves with fauna), 2019, earth pigments on Stringybark, 148cm x 76cm

Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda, Gathul (Mangroves with fauna), 2019, earth pigments on Stringybark, 148cm x 76cm

Wolseley in his sprawling drawings with crystalline passages of watercolour explores the life of molluscs and insects, inserting relief prints and rubbings from the burrowings of the larvae of beetles and moths under the bark of the trees. He introduces us into the dynamic marine life and vegetation of the coastal mangrove swamp.

Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda, Gathulnur (Mud mussels), 2018, earth pigments on Stringybark log, 247cm x 25cm x 25cm

Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda, Gathulnur (Mud mussels), 2018, earth pigments on Stringybark log, 247cm x 25cm x 25cm

It is a bold an innovative exhibition that presents something of a scorecard of the richness and sacredness of crucial marine eco-systems that are presently under threat from development and pollution.At the same gallery, but in the building across the road, is a striking landscape exhibition by Mary Tonkin. Tonkin, an artist in her mid-forties, works with a backyard mentality of painting only that which she knows intimately well. She grew up on the family bulb farm in Kalorama, perched atop the Dandenong Ranges east of Melbourne.

Mary Tonkin, Ramble, Kalorama, 2017-19, oil on linen, 21 panels, each 180 x 90 cm, total dimensions 180 x 1890cm

Mary Tonkin, Ramble, Kalorama, 2017-19, oil on linen, 21 panels, each 180 x 90 cm, total dimensions 180 x 1890cm

After her art training at Monash University and at the New York Studio School, she has spent much of her life painting en plein air at her property. She quite literally moves around with what appears as a converted cherry-picker that supports her sizeable canvases – about 180 x 190 cm.The showstopper at this exhibition is her immersive nineteen-metre-long Ramble Kalorama, 2017-19. It is not really a panorama in the William Robinson sense, or a continuous narrative as in Monet’s Waterlilies, but a gathering of sense impressions to create a huge scene into which you can dissolve.

Mary Tonkin, Ramble, Kalorama, 2017-19 detail

Mary Tonkin, Ramble, Kalorama, 2017-19 detail

Tonkin writes in her catalogue note that this painting, “is the culmination of more than ten years of drawing and painting around the problem of how to make a work that conveys the immersive and somewhat episodic experience of being in the bush. Even if I’m standing in one spot to draw or paint I move about, my point of view, relationship to forms, light and seasons all change. The previously seen impinges on the present and all the internal stuff I bring to it is in flux. I ramble about and try to make sense of it all, in a kind of ecstatic reverie.” It is an untidy cross-section of the bush – messy, chaotic and inspiringly beautiful. The artist has allowed herself to dissolve into an environment that she knows intimately well and leaves the viewer with enough breadcrumbs to follow and to become entangled within this enchanted setting of fallen logs and damp fecundity.

John Wolseley, Mulkun Wirrpanda and Mary Tonkin are three very different artists who demonstrate that there is plenty of life in the art of the landscape.

John Wolseley, Beetle engraving I, 2019, relief print found wood on Japanese tissue, 30.5cm x 40.5cm

John Wolseley, Beetle engraving I, 2019, relief print found wood on Japanese tissue, 30.5cm x 40.5cm

Two old artists looking for shellfish – John Wolseley and Mulkun Wirrpanda,

Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 28 Derby Street, Collingwood

23 July – 11 August 2019

Ramble – Mary Tonkin, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 35 Derby Street, Collingwood

23 July – 11 August 2019

http://www.sashagrishin.com/blog/gab-44-grishins-art-blog-44